Introduction

This was my first try at regurgitating an official neuroscience paper into a blog post, and it took quite some time to even grasp and understand a multitude of topics. I had to first read about feature binding in general and then understand this paper which proposed a mathematical model that expresses the binding problem. This post is a brief introduction to what the binding problem is, breaks it down into integration and segregation, and details why the neural synchronization theory is essential to it.

The Binding Problem

As you know, the brain is constantly processing color, shape, and movement from the outside world every second. Yet, have you ever wondered how it processes these different features in separate areas of the brain, in addition to emotional responses and other bodily functions, and transforms them into a single, cohesive experience?

This is what the binding problem aims to solve. In a nutshell, it is a longstanding research problem about how the brain combines objects, background, and emotional features into a single experience. It claims that the features of an object need to be bounded together by some neural structure consisting of a certain number of neurons.

Integration and Segregation

The brain must integrate streams of external stimuli and bind all of this information into meaningful representations, or mental models, to construct the next appropriate action. For example, during a tennis match, a tennis player integrates visual and auditory stimuli from the tennis court in addition to proprioceptive, sense of body awareness, information to perform the appropriate motor responses to hit a successful return.

This process can be described as the integration and segregation of brain networks. The brain must balance its ability to integrate information from various sources and segregate information into modules or mental models so that they can perform certain computations. By undergoing this process, this is how the brain orchestrates actions for the body to perform.

Neural Synchronization Theory

An explanation for binding features to neurons that is widely used in academia is the neural synchronization theory. This suggests that when external stimuli come into the brain, neurons associated with certain features form an assembly via neural oscillation. As a result, this neural representation encodes the object from the outside world.

Neural Oscillations

Neural oscillations are rhythmic patterns in the brain associated with specific neuronal activity and processes. By observing neural oscillations and measuring their frequencies, you can deduce the neural activity that’s taking place, such as one’s memory processing or motor control. For example, it’s been studied that high beta activity in frontal regions of the brain are linked to focused attention.

Limitations

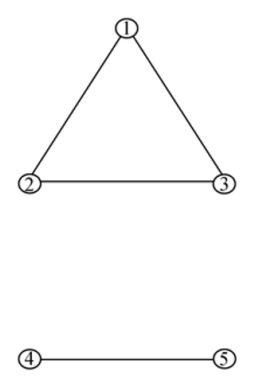

A major limitation of the neural synchronization theory is if there are multiple synchronization patterns being formed at the same time, which one becomes the final perception? Let’s say there are 5 input stimuli, 1-5, and [1, 2, 3] and [4, 5] are the patterns that emerge. Does the brain encode the object’s features as [1, 2, 3] or [4, 5] pattern?

Thoughts

I learned a great deal about the binding problem and how important it is to researchers in neuroscience. It encompasses multiple disciplines within the field, such as neurobiology and computational neuroscience, and utilizes all of these concepts to gain deeper understanding on the problem. One interesting detail that the research paper and other resources referenced is the brain’s distributed approach towards processing internal and external stimuli. As a software engineer, building and managing parallel and distributed systems is an important task for us. For the future, I’d definitely be interested in learning how neuroscience researchers studied the brain’s distributed processing and applied distributed computing principles to make practical sense of it.

In the next post, I’ll be diving deeper into the proposed model in the paper and breaking it down for better understanding.

Link to the paper: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18785593/

Leave a comment